Map size in jpg-format: 14.0154MiB

Click to open in high resolution (open in new tab).

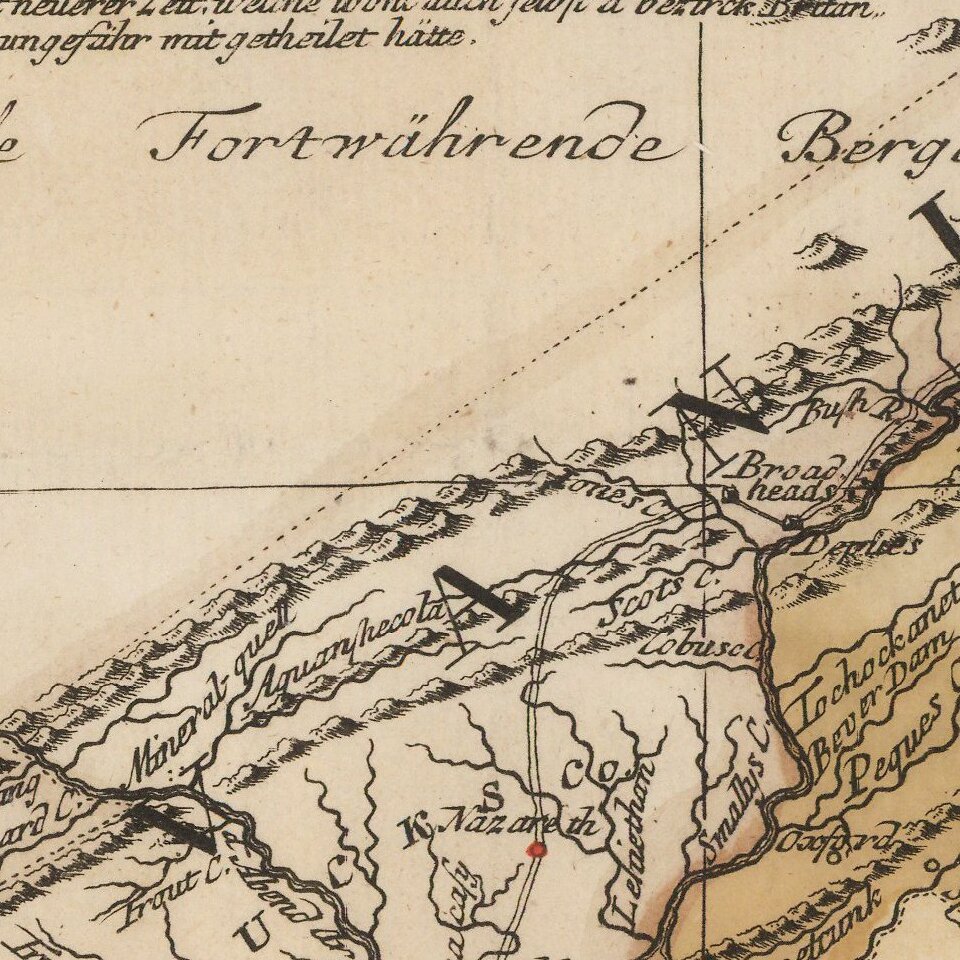

Extremely Rare German Edition of Lewis Evans' Landmark 1749 Map

Fine example of the German edition of Lewis Evans' important map, A map of Pensilvania, New-Jersey, New-York, and the three Delaware Counties, published on March 25, 1749 in Philadelphia. Evans' map is generally considered to be the first printed map of Pennsylvania made in America and his work was influenced by Benjamin Franklin.

Evans's map was one of the most important Colonial American maps of the middle of the 18th Century and was compiled utilizing information obtained by Evans in his travels and from a number of colonial American sources, many of whom never published printed examples of their maps, making this map a fascinating conduit for the work of several early surveyors whose work is no longer extant.

This Frankfurt edition, published in 1750, was meant to encourage German immigration to Pennsylvania and is extremely rare. Only 2 surviving examples of this map are known to exist.

Lewis Evans, Benjamin Franklin, and the 1749 Map

Little is known about Lewis Evans (1700-1756) before he appeared in Benjamin Franklin's shop on November 27, 1736. He bought a copy of Edward Cocker's Arithmetick, which was recorded in Franklin's shop notebook and gives the first indication of Evans' interests and location. His will reveals that he was born in Llangwnadl, Wales, but he also traveled widely in Europe as a young man. In 1738, he executed one of his earliest cartographic works, A Map of that Part of Bucks County, released by the Indians to the Proprietaries of Pensilvania in September 1737.

Evans trekked extensively throughout the American colonies, working as a surveyor. In 1743, Evans accompanied John Bartram and Conrad Weiser on a trip to Lake Ontario. Some of his wanderings are evident on this map, for example in the length and detail of the Susquehanna River and in the area around Shamokin. On these trips, Evans gathered geographic information from indigenous peoples and the few Europeans who lived on the then frontier of America.

As noted by Evans in a letter published in The New-York Weekly Post-Boy, dated May 15, 1749, the map was drawn from Henry Popple's famous map of the British Empire in North America, but with significant improvements. A second, revised edition was printed in July 1752. The original 1749 Evans map last appeared at auction in 1991 at Sothebys, which described it as follows:

. . . one of the first maps printed in the English colonies south of New York and the first printed map by Lewis Evans, America's greatest eighteenth-century cartographer. Very little is known about this map apart from the information provided in Evans's extensive legends, which include many notes on weather conditions as well as geography. It was long thought that the map had been printed in New York by James Parker, but Lawrence Wroth has shown that it must have been printed in Philadelphia and that Benjamin Franklin and David Hall-who printed the 1755 Evans map for inclusion in his Geographical, Historical, Political, Philosophical and Mechanical Essays-were probably the printers of this map.

Lingelbach agrees that Franklin and Hall are the likely publishers of the map. Evans had first advertised the subscription for the map in Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette in March 1748/9 and the two men frequently conversed about matters of natural philosophy, particularly electricity.

It is probably due to Franklin's influence that Evans was able to include conjectures about the movement of storms and about the nature of lightening on the map, observations which Franklin was also sharing with friends in the late 1740s. Evans also includes a discussion of eclipses as they relate to the measurement of longitude in the hopes that readers with astronomical interests might be able to help to better pinpoint the longitude of American cities.

Additionally, it is known that the copy of the original Evans map held by the American Philosophical Society was presented by Benjamin Franklin to Dr. John Mitchell, whose 1755 map of North America is generally considered the most important American map of the eighteenth century, along with Popple's map and Evans' own 1755 map of the Middle British Colonies.

Evans' sources and references

Franklin was not the only natural philosopher to help bring the Evans map to fruition. Another source Evans mentions is James Alexander. Alexander (1691-1758) was a lawyer, politician, and mathematician who had fled Scotland after the failed Jacobite Rebellion in 1715. He held offices in New York and New Jersey simultaneously and later became Attorney General of New Jersey from 1723 to 1737. As a lawyer, he gathered and commissioned a collection of maps that were used in his cases. An early member of the American Philosophical Society, founded by Franklin, he corresponded with the savant. On August 15, 1745, Franklin wrote to Alexander, "I return you herewith your Draughts, with a Copy of one of them per Mr. Evans and a few Lines relating to it from him." Evans was clearly corresponding with Alexander well before the 1749 map was published.

The "whole of New York Province" as shown in the Evans map owes a debt to Cadwallader Colden, as Evan acknowledges. Colden (1688-1776) was a natural philosopher, physician, and politician. Born in Ireland, he studied in Edinburgh and London, and then started a medical practice in Philadelphia. In 1717, he relocated to New York and in 1720 he became that colony's Surveyor General, hence his expertise on the province as referenced by Evans. Colden went on to serve as lieutenant governor and acting governor of New York in 1760-61, 1763-5, 1769-70, 1774-5. Colden corresponded with Franklin and encouraged him to found the American Philosophical Society; Colden's own interests were in cartography and calculus, specifically in correcting perceived errors on the part of Isaac Newton.

In addition to Alexander and Colden, Evans names several other gentleman in a text box in the lower left corner who gave him access to their own map collections for reference. These include Nicholas Scull II (1687-1761), surveyor and cartographer who served as the Surveyor General of Pennsylvania from 1748 to 1761, and John Lydius, who is possibly the colonial official and trader John Henry Lydius (1694-1791) who lived in upstate New York but who also did business in Pennsylvania. Isaac Norris (1701-1766), merchant, who served in the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, worked closely with Benjamin Franklin to develop the colony. His library was famous in Philadelphia. Evans also thanks Nicholas Stilwil, Joseph Reeves, and George Smith for use of their collections.

Evans also mentions two specific maps as references, although he was not acquainted with their makers. Among these are "Mr. Lawrence's new Division of Jersey", which divided the province of New Jersey into East and West Jersey. The line was created by John Lawrence, a surveyor, in 1743 and settled a dispute that had been raging since the 1670s.

Next, Evans references "Mr. Noxon's Map of the Three lower Counties." Thomas Noxon (d. 1743) was a landowner with holdings in the Middle Colonies and the West Indies. He was elected to the Assembly of the Three Lower Counties, which is now the state of Delaware. Pennsylvania had jurisdiction over the Lower Counties, and Noxon surveyed the area with Benjamin Eastburn in order to clarify the boundary line between the two. He had learned to survey while in the West Indies.

As mentioned, Evans' 1755 map was accompanied by a geographic treatise, printed by Benjamin Franklin, which also had editorial comments about the state of the colonies. In particular, Evans thought the British government too lenient toward French encroachment in the Ohio River Valley. Other of Evans' writings went farther, hinting at the collusion of the British government with the French. Unsurprisingly, these comments upset the colonial administration. Evans was imprisoned for libel of Pennsylvania's governor, Robert Hunter Morris. He died in 1756 in New York, just three days after he was released from prison.

The Frankfurt Edition

Klinefelter explains that this Frankfurt edition was the "highest compliment" ever paid abroad to the 1749 Evans map. A newly commissioned comparison of the English and German text reveals small, yet interesting, differences. First, certain of the anecdotal notes have been moved when the text was reordered and placed in numbered blocks. Text block 6, which discusses where indigenous peoples, by their own tradition, found corn, tobacco, squash, and pompions, has been moved from a geographic location (near the Onwganixom Mountains) to be justified with the left border. Other changes include an explanation of English terms, such "the tide runs to" and "the time of high water", and the conversion of English miles to German miles via equatorial degrees.

The largest change is an additional block of text not found on the English original. It describes the post road system that existed between New York, Philadelphia and other sizeable towns. The German text, block 21, reads:

Message from the newly erected post offices in North America, to which Philadelphia belongs: Since the creation of the general postmaster office in North America, the mail from West America leaves Philadelphia every Friday; the mail for Burlington and Perth Amboy is being delivered [along the way] and [the rest] arrives Sunday night in New York, the road between Philadelphia and New York is about 106 English Miles. From New York the mail goes further up east every Monday morning and arrives Thursday noon in Seabrook. This makes 150 Miles. In that very place, the mail leaves at the exact same time again for Boston and, like the New York mail is sent back with the mail from the east, this one returns with the mail from the west. The parcels are deposited in North London, Stormington, Rhodes Island and Bristol; the mail from Boston to Piscataway, a distance of about 70 miles, delivers letters to Ipswich, Salem, to Marblehead and Newberry. The Offices are established in Burlington, Perth Amboy in New Jersey, North London und Stormington in Connecticut, on Rhodes Island, in Bristol, Ipswich, Marblehead and New Berry. The three main offices are in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, from where the royal post master prints the books, Benjamin Fränklin.

Some of the information for this additional text comes from another map, Herman Moll's New England, New York, New Jersey and Pensilvania (London, 1729), which is generally considered to be the earliest American map to show post roads. Also known as the post road map, Moll's map contains "An account of ye Post of ye continent of Nth. America as they were Regulated by ye Postmasters Genl. of ye Post House." In the lower right corner, a text box covers the same locations and distances as the Frankfurt edition.

The German text in the Evans map goes on to discuss Benjamin Franklin and identifying him as the Royal Post Master in the Colonies, showing the author was aware of current events and providing the map with yet another Franklin connection.

This map was most likely reprinted quickly in Frankfurt as an encouragement to the already thriving German immigration to the British American colonies, and particularly to Pennsylvania. The additional post office text would appeal to prospective immigrants. It would give them some idea of the distances involved, the towns, but also reassure them that the whole of the country was connected and that mail could keep families in touch over the miles.

The first German settlement in the colonies was Germantown, established in 1683 by Quakers and Mennonites escaping religious persecution in their homelands. They chose Pennsylvania thanks to the preaching of William Penn in the Rhine Valley. Others came because their lands had been destroyed during the Thirty Years War and other conflicts. More settlements followed, for example Skippack in 1702 and Oley and Conestoga in 1709. These colonists came mainly from the southwest of Germany, areas then known as the Rhineland, Palatinate, Wurtemberg, Baden, and German Switzerland.

Roughly 65,000 German immigrants arrived in Philadelphia between 1727 and 1775; even more came through other ports. The largest wave of immigrants arrived between 1749 and 1754, precisely when this map was printed in Frankfurt.

Identity of the Publisher

But who published this map? Frankfurt was home to several map publishers at the time, but the most likely candidate is Heinrich Ludwig Broenner. Active from 1735 to 1779, Broenner was prolific. Included in his output, in 1750, was a book on Nova Scotia and the British and French colonial politics in the region. Clearly, Broenner thought there was a German market interested in the American colonies. He would later copy Samuel Holland's map entitled The Provinces of New York, and New Jersey . . .

Additionally, in 1748, Broenner published "Ausfurhliche Nachricht von Zinzendorfs Unternehmungen in Pennsylvania 1742-43," or "A detailed account of Zinzendorf's operations in Pennsylvania 1742-43." Zinzendorf refers to Nicolaus Ludwig, Reichsgraf von Zinzendorf und Pottendorf (1700-1760), a bishop in the Moravian Church. Interested in missionary work from the 1730s, in 1739 Zinzendorf himself travelled to St. Thomas in the West Indies to visit his mission there.

Next, Zinzendorf traveled the American colonies on the mainland, where he met with Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia. In 1741, along with fellow Bishop David Nitschmann, Zinzendorf founded a small mission in Pennsylvania that was supposed to convert indigenous peoples and German-speaking immigrants already in the area. They named their mission Bethlehem and the settlement is now the sixth largest city in Pennsylvania.

Broenner's tapping of an interest in the Pennsylvania mission, and a wider interest in the American colonies, makes him the most likely candidate as publisher of this map.

Rarity

The map is of the utmost rarity. The only confirmed copies are held by the Library of Congress (acquired in or before 1929) and the University Library Johann Christian Senckenberg in Frankfurt. The original 1749 Evans has appeared only twice on the market in the past fifty years (Sothebys 1991: $30,800 and Streeter 1967: $5,500).

Translation of the German text, with differences from the English edition in italics

Special land map of Pensilvania, New Jersey, New York and of the three counties along the Delaware River

In America printed in English A[nno] 1749. In Europe published in German in Frankfurt am M[ain]. A[nno] 1750.

If you are a student, write to us in telegram: @antiquemaps and indicate what material you need and for what work you need a map in high detail. We are ready to provide material on special terms. For students only!